Reality-Based Integrated Instruction

Paper presented at the Annual Conference and Exhibit of the National Middle School Association Abstract: A teacher wants to help her middle school students who already hate poetry to appreciate Williams’ poem “This Is Just to Say,” but her approach is ill-focused. This article outlines how to properly plan a unit using brainstorming techniques; essential and guiding questions; and hands-on, engaging activities that motivate students. Part I: A Traditional Poetry Lesson

Part I: A Traditional Poetry Lesson

Mary Reynolds, a language arts teacher, has always been especially fond of poetry and is certain her students will share her enthusiasm. She plans her lesson carefully and anticipates the spirited response of her class to this new and exciting territory. Unfortunately, the class does not greet Mary’s announcement that they will be “exploring poetry” with the eagerness she had hoped for. In fact, they all groan. They have “explored” poetry before. They have endured endless sessions on iambic pentameter and trochee. They already hate poetry, but Mary is determined. She hands out copies of her first selection, “This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams, and reads with perfect intonation and timing.

I have eaten the plumsthat were in the iceboxand whichyou were probably savingfor breakfast Forgive me they were deliciousso sweetand so cold(In The Selected Poems of William Carlos Williams)Mary doesn’t see the note Sally passes to Katie. Sally uses three different colored markers to write: Bor-ing. Ab-so-lute-ly boring, boring, boring! Katie writes back, YESI YES! YES! SAVE US FROM POETRY!

Mary slowly lowers the paper she has been reading from and smiles at thirty pairs of glazed eyes. “Well,” Mary says, “what did we think of that poem? Hmm?” A voice from the back calls out, “He shouldn’t have eaten the plums without asking her first.” The class snickers and Mary says, “I think you missed the point of the poem.” She looks around for a face that registers some understanding, but it’s too late.

Mary can’t even manage to return to the areas she had planned to discuss and announces to the class that she expects them to write a 250-word essay on the poem for homework. “Be sure to have a thesis statement,” she says. “And don’t forget the components of a good essay: introduction, body, and conclusion.” Now she is on firm ground. They are listening and taking notes.

“What if we didn’t understand the poem?” Sally asks. “Then you weren’t listening,” Mary snaps. She is more relieved than the students when the period is finally over.

That night Mary considers everything she might have done differently to make the lesson more valid to her students. She regrets the homework assignment she gave in anger and knows that it will have no relevance to the unit she planned. It was punitive and arbitrary of her to ask them to write an essay about something that has no meaning for them. She knows she was unable to help them make a connection between the poem and anything in their own lives, but she does not know how to design a lesson that will help accomplish this goal.

Mary senses that if life experiences are concentrated on one area at a time, then it would make sense to focus on independent subjects. However, she knows our daily experiences are not usually restricted to one area at a time. Ordinary events and problematic situations are much better understood if we integrate knowledge from the academic disciplines and relate them to experience (Ackerman, 1989).

Mary suspects that poetry would have greater meaning for her students if they began with an experience based on reality. She might ask them to examine some of their daily experiences and to note how their senses are affected in different ways. For example, she could ask each student to use concrete words to describe an ordinary activity that does not require language and to describe how it felt. It might be something as commonplace as brushing teeth or combing hair, but they have to use words that capture the experience and make it come alive. Mary anticipates asking a student to stand up and comb his hair. He might say, “When I comb my hair it feels as if hundreds of fingers are trying to pull my hair out of my scalp,” or “I wonder if the comb is shouting, ‘Yippee’ as it slides down my hair.”

Now Mary imagines endless possibilities, but she is still unsure about how to actually design the lesson. Since most life experiences require a broad knowledge base, which envelops more than one discipline, she knows that children need to be taught how these disciplines can play an interactive role and enhance the world around them. These are the components Mary must address in designing her lesson.

Why Redesign Curriculum?

As educators, we know that students are interested in the entire world around them and in why things do what they do. Introducing children to facts that are not connected to any of their prior knowledge is ineffectual and wasteful. If connections are made to situations that students have already experienced or heard about, then classroom instruction has a greater chance of being understood and enjoyed. Mary has a sense of the importance of this but we have to give her a model for redesigning the lesson.

Thematic or integrated instruction includes events pertinent to that experience and strives to accurately reflect the real world. Isolated disciplines have meaning in isolation, but the true test is their application to real-life experiences. There are fewer isolated areas in thematic instruction because it begins with reality and draws on the discipline natural to that experience. There would be a greater number of students attracted to poetry and other literary fans if teachers were able to make the content relevant to the lives of their students.

The more realistic we become about the content of the subject we teach, the better we can create. When educators anticipate the potential for poetry in their subjects, lt will be as easy to recognize as the potential for poetry in life.

Part II: From Creating a Thematic Map to Defining Your Focus

Teachers can work together to achieve a thematic unit that is both interdisciplinary and student-centered. Learn how to pick a theme, brainstorm that topic, and then create an outline with both scope and sequence.

I. Choose a Theme

First, whether one decides to work alone, with another teacher, or with a team of teachers, choose a theme that has interest value for everyone. Nothing is worse for students than an unenthusiastic teacher. If the teacher is not interested in what she is doing, there is little chance that the students will care about the topic. Students are likely to model their teacher’s excitement and to recognize genuine commitment and eagerness. When underachieving students notice that the teacher cares about the course work and personally has the desire to learn, student achievement rises (Emerick, 1992).

Step 1: Choose a topic: Poetry

II. Narrow your Focus

Poetry is a large topic that offers many possibilities. However, if we break the topic up into “mini-themes” and work on one at a time, it is more likely that we will find creative choices with the intensity to challenge us as well as our students.

“Imagery” or “tone” are just two of the possibilities that can result when a theme is narrowed. “Exposing our students to less should help them learn more” (Dempster, 1993). When we explore less material in greater depth, students will learn in a more meaningful and connected way. This approach prevented the hazard of making something rich superficial (Perkins, 1989).

Step 2: Narrow the focus: Symbolism in Poetry

III. Create an Interdisciplinary Web

Creating a web is a reliable technique that has endured because of its effectiveness. The name of the theme is placed in the center of the page and circled. Then the disciplines that naturally extend from the theme are recorded in a spiral fashion: math, art, science, sociology (Hayes Jacobs, 1989). Next, create mini-webs from each of these disciplines. Allow ideas to flow freely and write down the ideas that stem from each discipline. Branch each idea by circling it and then connecting it with a line to the previous idea. Create as many branches as possible, allowing larger thoughts to branch into more specific ideas for support of the original thought.

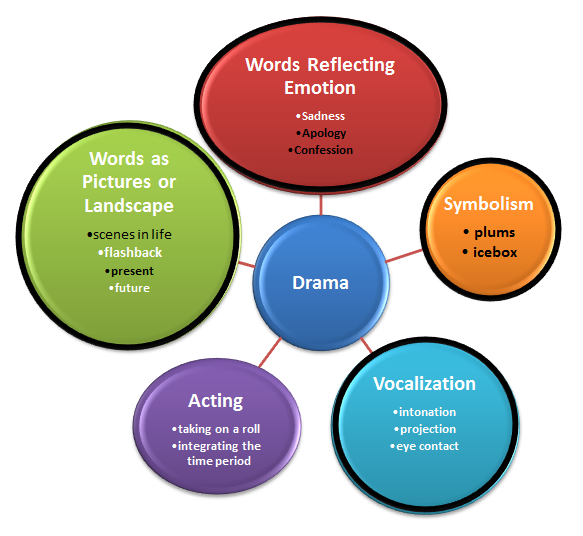

For example, if the theme is symbolism, one of the disciplines could be English or language arts. Other disciplines might include drama, social science, math, or art.

Step 3: Create an interdisciplinary web: Brainstorm through webbing

Write down all the ideas that are generated without expressing any judgments. Keep in mind that there is no isolated area in thematic instruction–it includes everything that is natural to experiences based in reality. Webbing allows relationships among subjects and topics previously unrecognized to be acknowledged for their potential.

Under each discipline, brainstorming could lead to such topics as words-as-pictures, words reflecting emotions, and vocalization. From each of these clusters, continue brainstorming and allow all ideas to flow freely. For example, under words-as-pictures, ideas generated may include scenes in life, both present and future, as well as flashbacks and items that reflect the time. Don’t hesitate to allow students to incorporate pictures, symbols, or numbers into the web.

Step 4: Brainstorm each discipline

V. Decision Making

Don’t be concerned if some of the topics initially listed on the web seem inappropriate. After the initial brainstorming session, highlight the essential areas.

Step 5: Examine the web from Step 4. Highlight those areas that would create an excellent focus for your theme.

VI. Develop a Scope and Sequence

Make a brief outline from those areas. This outline will serve as an initial scope and sequence for each discipline area. As you progress through this process, the scope and sequence may shift and other pieces of information may be included.

You may ultimately decide to break away from this process. Allow yourself enough time to create an in-depth scope and sequence. This outline should serve as the guide for the most essential outcomes and information that students eventually achieve or learn.

Step 6: Create an Outline

1. Poetry as Symbolism A. Drama for an Apology1. Word-as–Picturesa. present day scenes1. senses2. objects3. reality-based experiencesb. display of emotion1. temptation2. through the senses3. confessionsVII. From Overall Goals to Writing the Essential and Guiding Questions

Write down three overall goals that students will reach after completion of this unit. This will keep the teacher focused and guarantees that the activities are designed to reaffirm the major points. Then craft these goals into questions that are written for every child to understand (Hayes Jacobs, 1989). This can be accomplished by writing the “essential question,” which is written in umbrella-like language and is simple and non-repetitive. I recommend that the first question or essential question be written as a definition question. This is followed by “guiding questions,” which narrow the focus but still supports the essential question. I further suggest that these questions be open-ended, personalized to the reader, and link the unit together. Be sure to post the questions in the classroom for all the students to see.

Step 7: Essential and Guiding Questions:

Essential Questions: (Definition)

What is Poetry? What is an Apologetic Poem?

Guiding Questions: (Supportive and Open-Ended)

1. In what ways is poetry similar and different to other forms of language?

2. How many different ways does poetry highlight or illuminate ordinary experiences?

3. For what reasons have people found different ways to express themselves?

4. For what reasons do people find comfort in the written word when trying to apologize?

Part III: Crafting the Hands-On Portion of the Lesson

Now that you have a clear understanding of what you want your students to “uncover” in the lesson, it is time to make it personal and come alive, engaging them.

VIII. Create Student-Centered Activities to Reinforce the Scope and Sequence

One of the most exciting benefits of an integrated curriculum is its adaptability to different teaching methods. Student-centered learning can be easily applied to interdisciplinary instruction. This technique requires students to become active members of the learning experience by taking part in hands-on activities. These activities may range from something as elementary as building a model to a Socratic debate.

What if Mary Reynolds had remembered that her personal goal was to give her students a chance to love poetry as much as she did? Mary could have given her students an opportunity to look at poetry in a way they had never previously considered. Before she even read the selection by William Carlos Williams, Mary could have initiated a discussion of “real” things from their own lives which would support the poet, Marianne Moore’s explanation that poetry “is imaginary gardens with real toads in them” (Norton, 1972).

Step 8: Activities:

When learning about poetry, students should be involved in activities that will express their understanding. In this case, it is critical to communicate that all of us have had the temptation to take something that did not belong to us. So, in preparation for the poetry lesson, Mary might have asked students to chart experiences from their own lives:

- Describe a time when temptation overwhelmed you, and you borrowed something from a sibling or a friend without asking.

- Have you ever taken something from someone without asking because you wanted it so badly? Explain specifically what happened.

- Can you remember anything that you ever wanted enough that you would risk the consequences of taking it without asking?

- Explain in detail how it made you feel to do something that crossed the boundary of right and wrong.

- Display to a peer the emotion behind it, as if you were on stage and had to convey that feeling.

These types of open-ended questions encourage students to think about their own lives in relation to the content of the material. Poetry gives the writer-student an opportunity to capture experiences from all areas of their “real” lives as they actually happen and preserve them in a freeze-frame.

When we ask students to forget everything they have ever learned about poetry and concentrate instead on freedom of expression and the language that can be used to share it, we are giving them an opportunity to better understand their own lives. For example, we could ask them to think about how language affects their lives in significant ways and give them several moments to reflect on the last painful exchange they shared with a friend or a family member. In this way, we are encouraging them to use life experiences that have impacted on them in significant and meaningful ways. Some activities that might encourage this include asking students,

- How many different words can you think of that are hurtful? Comforting?

- In what ways do words affect us?

- Describe the way different situations make you feel and how words can be an effective vehicle for expressing these feelings.

Small cooperative learning groups or pairs can exchange information about how words can either hurt or comfort, and students can share their own experiences. When they realize how the selection of a word can alter the most ordinary statement, they can begin to understand how their own lives are shaped by the elements of a single experience. This is similar to the idea of a web where the ideas and concepts are often related. In much the same way, we bring a combination of many experiences and feelings to each new situation.

While the form of poetry may be physically different than other more familiar written forms, students can be introduced to ideas that will enhance many areas of their lives. They can be encouraged to see that not everything or everyone needs to look the same to be able to communicate with passion and understanding.

When Mary Reynolds offers her students “This is Just to Say” she is obliged to make her students see that there is no line dividing the poet from his endeavors as a poet, and his life as an ordinary person. In “This is Just to Say,” William Carlos Williams has captured one of the countless daily activities that are as prone to poetic treatment as any other. Mary’s goal is to help her students discover something special in these ordinary words. When students use their imaginations to really “see” the source of their imaginings, they will begin to understand that poetry is about real life. Mary can help her students realize that poetry is about seizing experiences and feeling as they actually happen.

As a follow-up activity to the poem by William Carlos Williams, students can be asked to describe the ways our society apologizes- but as an extension to the lesson- in times of war… or in times of peace.

- Generate a list of different lines from famous speeches that you remember?

- Explain in detail the circumstances of when these speeches were delivered.

- Describe in detail what made these speeches memorable.

- In what ways do words help us heal?

- In what ways does language provide a vehicle for communication that is different than any other way?

We can ask students to write their own apologies. First, ask each student to write the name of the person who will receive the apology. Next, tell the students to circle the name. Now students can create their own webs. They will need to brainstorm the reason for the apology, their feelings of regret, and their concern over the specific incident. This can be an especially emotional experience. It’s a good idea to have tissues on hand. Students can anticipate the person’s reaction and how it will make them feel. The different ways of apologizing can also be brainstormed. Next, students can highlight the areas to be addressed. These final categories can be incorporated into a poem similar to the one written by William Carlos Williams.

Poetry can help students see that it is the moment that is featured. Poetry tends to isolate segments of life and encourages students to examine them from a broader perspective. As teachers, we cannot record the experience for them or tell them why that moment has value in their lives. To do so would be to guarantee their confusion. After all, how can students learn if we tell them everything?

If Mary Reynolds had asked her students to write someone a short note of apology for some vague indiscretion, either imaginary or real, and then asked them to explore how words can represent a sense of collective humanity that exceeds even their wildest expectations, she would have offered a successful lesson on poetry.

Art Integration

Students may also compare how different forms of art reproduce life with varying degrees of emphasis and interpretation. Samples of Norman Rockwell‘s covers from The Saturday Evening Post would provide an excellent source of art as a reproduction of ordinary life. After students have completed their own poems, they can then illustrate them. Finally, students may be asked to identify the poems depicted in each other’s illustrations.

As we had integrated Social studies previously, students can also investigate the lives of the poets and an analysis of the historical period during which they wrote. Then students can make the connection to their own environment and to the essence of their own poetry. Students might be encouraged to research the life of a poet and develop an understanding of how the historical period in which the poet lived is reflected in his or her work. As an extension to the core content, teachers may want to have students write letters to a contemporary poet and question how his or her writing is influenced by society. Guest speakers might include a poet, an editor of a poetry journal, a biographer of a poet, or the students-as-poets themselves!

In addition, each child may be required to keep a journal where new information can be recorded and where organization of thoughts can be encouraged. The role of memory in recording Information and journal keeping would be an interesting component of how poetry actually evolves.

© 1994 Speech by Andi Stix, Ed.D.ERIC: Eric Resources Information Center #ED377491Paper presented at the Annual Conference and Exhibit of the National Middle School Association, “Bridges to Success” (21st, Cincinnati, OH, Nov 3-6, 1994)

Making connections between the written word and one’s life is critical when trying to engage our students. Compare and contrast the difference of when you tried to teach a poem, prose, or quote from the author’s point of view without involving students to when you asked them to make a connection to their own lives. Feel free to share some samples of what your students have produced.

Andi Stix is an educational consultant & coach who specializes in differentiation, interactive learning, writing across the curriculum, classroom coaching, and gifted education. For further information on her specialties or social media, please email her on the Contact page.

References

Ackerman, David L (1989) Intellectual and Practical criteria tor Successful Curriculum Integration. In Heidi Hayes Jacobs (ED) Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Design and Implementation. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Dempster, Frank N. (1993) Exposing our students to less should help them learn more. Phi Delta Kappan, 74:6, 433-437.

Jacobs, Heidi Hayes (1989) Design options tor integration curriculum. Interdisciplinary Curriculum. ASCD.

Norton, James & Gretton, Francis. (1972). Writing Short Plays, Poems, Stories. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Perkins, D. N. (1989) Selected Fertile Themes for Integrated Learning. In Heidi Hayes Jacobs (Ed.) Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Design and Implementation. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Williams, William Carlos (1985). Selected Poems. Charles Tomlinson (Ed.) New York: New Directions.